(Image by somadjinn)

In legends around the world, gods, mythical creatures and birds could soar through the air naturally, but humans could only breach this territory using magical aid. Scores of people, from da Vinci to Lana de Terzi, speculated on how humans could achieve sustained flight sans divine aid, often observing birds to try and emulate them. However, in 1690, scientists demonstrated that human muscles were insufficient for sustaining flight in imitation of the birds, which led many to abandon the idea in favour of lighter-than-air machines like the balloon (Singer).

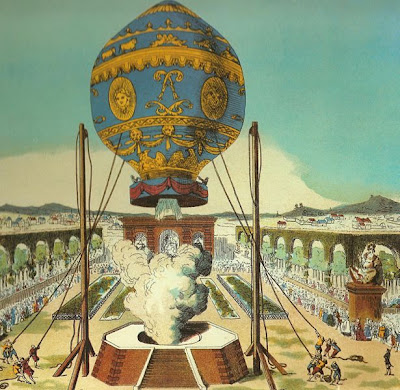

The balloon, brainchild of paper manufacturers Etienne and Joseph Montgolfier from Annonay in southern France, made its first ascent on 4 June 1783. This contraption worked on the principle that hot air is lighter than cool air, so heating up the air inside the balloon would lift it into the sky. A physicist named Professor Jacques Alexandre Cesar Charles and the Robert brothers also constructed a balloon, this time using hydrogen gas instead of rarefied air to send it aloft. They competed with the Montgolfier brothers to restore prestige to the Paris Academy of Science, which was suffering a setback during the eighteenth century, and to become the first human aeronauts in history (Christopher).

(Montgolfier brothers demonstrating balloon flight; image from Encyclopedia Britannica)

Excitement abounded for both types of balloons and many observers believed “humanity had triumphed over the last great frontier” (De Syon), although after aeronauts ascended to greater heights, the balloon opened up the possibility for exploring every facet of the universe. It was no accident that the balloon became popular during the middle stages of the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution. It was a time of terrestrial misery and social upheaval, key ingredients that determined the balloon’s role as a symbol of ultimate freedom, a freedom viewed by most as a human, and not divine, achievement. It was a perspective that caused Europeans, particularly the French and the British, to place extravagant hopes on the balloon that more often than not failed to meet their expectations.

Many people in France and Britain believed the balloon would provide an escape from the overwhelming changes caused by the Industrial Revolution, and the conditions prior to the French Revolution, but because not everyone was able to experience balloon flights or watch it ascend into the air, many stayed stranded in terrestrial misery. In Christian theology, there is a contrast between the perfect heavens and the imperfect earth, where the latter is seen as the center of the universe while Hell is at the center of the earth, both often characterized by pollution, corruption and change (Singer). During the Industrial Revolution, there was an influx of all these things, so escape from a world becoming increasingly like Hell became a common desire. The balloonist Henry Mayhew commented that London, the "leviathan Metropolis" (Mayhew and Binny), was consumed in its own fumes. His next words acknowledged the struggles of workers trying to increase production in an increasingly mechanized and capitalist state, as well as the social constraints at play in his Victorian society:

to hear the hubbub of the restless sea of life and emotion below, and hear it, like the ocean in a shell, whispering of the incessant strugglings and chafings of the distant tide—to swing in the air high above all the petty jealousies and heart-burnings, small ambitions and vain parade of ‘polite’ society, and feel, for once, tranquil as a babe in a cot…to feel yourself floating through the endless realms of space, and drinking in the pure thin air of the skies, as you go sailing along almost among the stars, free as ‘the lark at heaven’s gate’, and enjoying, for a brief half hour, at least, a foretaste of that Elysian destiny which is the ultimate hope of all (Mayhew and Binny).

Although Mayhew and other aeronauts like James Glaisher, who described the awe he felt when the sounds of labour faded below him while in his balloon on 9 October 1863, could escape temporarily, there were many obstacles for others desiring a ticket to the heavens.

In France, scientists, the monarchy and the highest classes of the Ancien Régime monopolized ballooning, which made it harder for the masses to find an escape from their miseries. During balloon ascents, the crowds consisted of the king and court, other nobles and government functionaries. In fact, the government tried to suppress the masses from becoming interested in ballooning, or from watching the flights. Newspapers failed to announce the event and before the Montgolfier’s trial runs at Saint-Antoine in 1783 (Glaisher et al.), a public announcement was made requesting the masses to stay away (Gillespie). It was a request that did not take into account the balloon’s high visibility, so crowds were inevitable, but it showed the prevalent social demarcations at the time. The crowds gathered because it was entertainment, an escape from the drudgery of mechanized labour, but officially, they were not allowed this form of escapism. Since they could not successfully prevent the public from viewing the balloon, the masses were then prevented from being able to fly in the balloon.

When J.F. Blanchard, a bourgeois mechanic, tried to satisfy the larger public’s appetite for the balloon by crafting and flying his own balloon, the Paris police issued an ordinance forbidding all flights without permission from the Paris Academy (Gillespie). They claimed that only persons of “known experience and ability” (Gillespie) could attain permission, but what they really meant was no one outside of the elite classes could attempt to fly. At the same time, some provincial scientific academies pursuing aerostation confined their membership to the urban elite—nobility, clerics, provincial officials and professionals (Gillespie). Feelings of escape and freedom could be attained by physically escaping on a balloon or by viewing the balloon’s ascent, since its power as a symbol of freedom was usually sufficient for the working masses; however, because the authorities tried to restrict its dissemination into the public domain, hopes for achieving some kind of escape were shattered for many people.

(Ascent of the Nassau Balloon in the Vauxhall Garden; image from Victorian London)

In England, skepticism and fear from the elites hindered the ability of the balloon to fulfill people’s fantasies of escape. When the public first heard of the balloon in Britain, there was enmity between the two polities arising out of the Seven Years War from 1756 to 1763, and the American fight for independence from 1775 to 1783. The French were their adversaries for both wars, and although the British triumphed in the former war, French collaboration with the revolutionary colonies in North America exacerbated the anger and bitter rivalry already between them. In this way, anything that came out of France was viewed with skepticism and opposition.

At the same time, Victorian society was in the grips of a debate between the definition of science and the “morality of entertainment” (Tucker). Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society of London and head of British science, wrote a letter to Benjamin Franklin claiming that the Royal Society will “guard against the ballomania which has prevailed in France” (Gillespie), and that they will not patronize balloons until its usefulness to society is proven (Gillespie). Without the sponsorship and interest of the Royal Society, ballooning was left mostly in the hands of adventurers relying on the wider public’s support and smaller monetary contributions. The competition between these aeronauts worsened the situation, since each aeronaut had even less money to spend on their balloons, causing them to be badly made and prone to accidents.

Like the French, the British masses also looked at the balloon as a form of escapism, especially since balloon ascents attracted mostly heterogeneous crowds that blurred social boundaries (although the poorest classes continued to be excluded, since they could not afford the entrance fee to the pleasure gardens showcasing the balloon ascents) (Tucker). In 1836, these shows were so popular that failing to make the balloon ascend could cause a riot. In one example, the balloon caught fire before liftoff, signaling an aborted ascension and the start of rioting amongst the crowd. There was an attempt to seize officials and duck them in the pond, but failing that, they stoned the balloon (Delgado). Symbolically, a failed balloon ascent was probably analogous to snatching away the public’s chance to escape temporarily, and so riots occurred as a form of retaliation against what they felt was injustice. However, these riots only increased Victorian fears of the “savage” within. Including money-making charlatans selling tickets for balloon ascents that never took place (Christopher) and pickpockets roaming the streets waiting for the balloon to capture the crowd’s attention (Gillespie), the newly formed Times of London summed up their displeasure:

Nothing can more fully demonstrate the folly of the age, than their rage for ballooning…It is high time that some restriction should be laid on the madness of their frequent trips to the air without one single good purpose being produced. If a calculation was made of the number of manufacturers [workers] it takes from the employment, a very alarming loss to the nation would appear to the reader besides the dissipation, idleness and mischief which are the natural consequences of working men making holidays (Times article in Gillespie).The “idleness and mischief” caused by balloon spectators were at odds with the Victorian “gospel of work” (Tucker) that was a paradigm of social virtues in Britain at the time. Thus, a fear of French “ballomania” and social chaos, and general skepticism prevented the balloon’s proper development in Britain, and many people’s hopes for escape were dashed when the balloons failed to rise.

In a time of great class differentiation, people placed their hopes of rising above their given stations in life on the balloon, but the set social hierarchies of the time proved to be inflexible to public dreaming. The foreigner, Vincenzo Lunardi, introduced the art of ballooning to the British public on 15 September 1784 so that he could make his way into fashionable society and bolster his public image (Christopher).

(Vincenzo Lunardi; image from Science Photo Library)

When he floated back down to earth, he became a hero to the masses, and the upper class citizens were forced to tolerate him. He implored the monarchy to watch his performances, but his pleas were futile, and in the end, when he committed a breach of etiquette in a social event, the London elites were only too happy to reject him thereafter (Gillespie). Lunardi was both a foreigner and a man born of bourgeois parents; despite being a hero to the greater public, to the aristocrats, he was a lower class citizen at heart and would always be one. These attitudes were echoed in visions of the future.

For example, an advertisement by the Swiss brand, Sprüngli, depicted a balloon world in the year 2000 where people were able to sail through the air in balloons. In this fantasy, the social standards of the day, revealed by the citizens’ clothing, remained the same; only the vehicles of transportation changed (an advertisement in De Syon). These responses were similar to those of other new machines; despite fast technological progress, human attitudes and values did not evolve at the same pace. In this way, though ballooning was becoming an acceptable form of flight for women, especially by the mid-nineteenth century, women who wanted to fly and free themselves from their accepted roles in society continued to receive negative responses from the masses (De Syon).

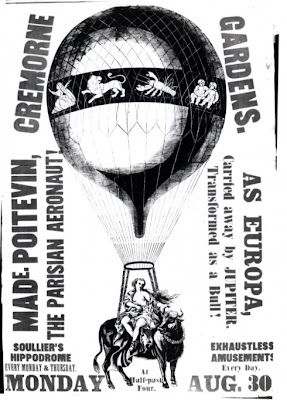

In the early years of the balloon, there was an ambiguity about whether flight was a divine or demonic gift. Thus, when scientists claimed that flight had been gained by purely secular means, it garnered suspicion from the public (Singer). In Christian tradition, flight is associated with chastity, but in the case of flying witches and warlocks, it indicates perverse sexual rituals in which the broomstick is often associated with phallic symbolism (Singer). With this in mind, it is no wonder that a woman descending in a balloon on rural farmland in 1850 was beset by angry and frightened farmers who believed she was a demon; others fell to their knees in fervent prayer (Scientific American article, July 2000). Another woman, Madame Poitevin, rose in a balloon riding on a donkey to enthrall the crowds, but when she landed, protests were made and she was fined for cruelty to animals (Delgado).

(Madame Poitevin; image from The Library Time Machine)

However, when a male balloonist performed the same stunt, the crowd uttered no protests or complaints (Delgado). It is obvious that the public continued to set two different standards for both sexes, and even though women most likely placed some hope of equality between the sexes on the balloon, it was only found up in the air. For Lunardi, other lower class aeronauts and women, ballooning failed to raise their social standing because down on the ground, people’s attitudes had not changed drastically enough for them to start thinking that lower class citizens can be anything more, or that a woman flying was appropriate.

With the advent of ballooning, some European thinkers envisioned a Utopian world where people’s new understanding of their roles as commanders of the skies would enable them to see the futility of war; in reality, the knowledge of having more power exacerbated the human desire for more control. In an ode to the balloon's discovery, an allegorical engraving was prepared by the Academy in Marseilles that showed a balloon up in the sky and a scythe, a traditional symbol for death, lying on the ground. It showed the belief that control of the air led to immortality and to death's defeat (Singer). Others such as publisher Alfred W. Lawson claimed flying would change the world and bring about the evolution of a new species of humans mentally and spiritually superior to earthbound ones (Alfred W. Lawson quoted in Van Riper). His musings are faintly echoed in Henry Mayhew’s description of his flight over London, where he described the people as "Lilliputian" (Mayhew and Binny) , the tiny people from Jonathan Swift's novel Gulliver's Travels.

(Gulliver and the Lilliputians; image from Orwell Today)

At first glance, his words are a simple description of the onlookers' physical appearance as seen from a greater height. Probing deeper, Mayhew may have been alluding to Gulliver’s observations of the Lilliputians. Gulliver had obvious advantages over them, a fact he could have easily manipulated, but refrained because the experience gave him a new perspective on the power-hungry nature of humanity. Height is something that extends vision, both literally and metaphorically, since being at a great height allows one to see more of the earth—a panoramic view. Metaphorically, this could imply that being in the clouds conferred a state of godliness, since God is able to see everything at all times. Mayhew felt the implications of flight and its endowment of power to humankind. With this new perspective, it was easy for some optimists to believe that the possibility of an air threat would help stop future conflicts: “to challenge gravity successfully would turn nations into neighbours rather than enemies” (Carl Falkenhorst quoted in De Syon).

The poet, Rhoda Hero Dunn, wrote in 1909, “hearts leaped to meet a future wherein unfenced realms of air have mingled all earth’s peoples into one and banished war forever from the world” (Dunn). Science fiction writer Jules Verne also saw the balloon’s potential. In his novel Five Weeks in a Balloon, the adventurers come upon two African tribes massacring one another in Chapter Twenty. Dick Kennedy fires at one of the leaders and the tribesmen stop momentarily at the display of “supernatural” death. The massacre’s direction is set from then on, since many of the fallen leader’s warriors retreat (Verne). In firing his bullet from above, Dick Kennedy emulated divine intervention; he determined the outcome of the battle. Whether implicit or not, Verne showed that being aloft on a balloon was akin to being as one with the gods, and that they had the potential to stop wars. Unfortunately, many European leaders at this time were more preoccupied with colonial expansion and competition with one another than with visions of perfecting human relations. Thus, the balloon became another weapon for humans to use against each other.

Instead of bringing an end to warfare, the balloon’s fate as a military weapon defied some people’s hopes. At first, the balloon was believed to be the unlikeliest candidate for war, since it was hard to control, but it could not escape the interests of the military (Christopher). Before the balloon was ever launched, Joseph Montgolfier had already been thinking about using the balloon to launch a surprise attack on the British forces at Gibraltar (Christopher), since many French were still bitter about losing the area to the British in 1704 during the War of the Spanish Succession. The inventor reasoned that "by making the balloon's bag big enough, it will be possible to introduce an entire army...right over the heads of the British" (Christopher). There were many proposals of attacking Britain using balloons, and on 3 December 1797, the French periodical L'Étoile de Bruxelles announced that a "numerous army was preparing to cross the sea and force the cabinet of London to see reason...a mobile camp is being constructed, with a vast Montgolfiere to lift it and an army, and transport them across to England to effect the conquest" (L’Étoile de Bruxelles (1797) in Christopher).

Even though it did not really happen, there were many who speculated on how it could happen. Some engravings from the time depict huge balloons, each carrying a thousand French troops, horses, cannons and supplies for ten days on a huge platform below the balloon bag (Christopher). It is uncertain how serious the French government actually took these speculations, but just the fact that they existed shows the hopes others had for the balloon’s military career. Although bombing was a popular idea, balloons were used primarily for observation. As part of the response to overhead bombing threats, the 1899 Hague Convention on the laws of war banned projectiles from being thrown from aloft, since hitting targets from above was considered dishonourable and unfair (De Syon).

However, since European administrators and missionaries believed in their own intellectual and biological superiority, and saw themselves as benefactors to the people of “decadent” Asia and “savage” Africa, and as bringers of moral revolution, these restrictions were removed when it came to using balloons against non-European enemies. In 1884, the French sent an expeditionary force to Tongking in northern Vietnam, where the balloon was used for reconnaissance and finding ways through the trackless marshes, as well as to bombard Hong-Ha with guns fired from the air (De Syon). Though some people hoped the balloon and control of the skies would bring about an era of no conflict, its introduction into a society where colonialism and national competition were the prime movers of European leaders sealed its fate as a military tool.

People saw the balloon as the mechanism that would help them realize their dreams, but because many people’s imaginings ran counter to the values and attitudes of the elites and leaders of their societies, their extravagant hopes could not hold a fortress against the force of the old order. The balloon came into a social context of industrialization and mechanized labour, as well as into European societies in which class differentiation and colonialism were still important. If the balloon could sometimes free people from the drudgery of the world, blur the boundaries within society, or cause a change in people’s perceptions about war, the people who would ultimately effect changes were often trapped by current prevailing notions. The balloon may not have completely fulfilled some people’s dreams of freedom from the machine, from social constraints and from human folly, but it did change thinking about scientific methodology, especially in Britain, since scientists relying on public funds often showcased scientific precision that would become the model for science today. It also widened the possibilities for exploring the rest of the universe, introduced a new form of mass entertainment, and made the threat of aerial attacks very real, despite the sad discovery that balloons themselves were actually inefficient war weapons.

Sources Cited

“50, 100 and 150 Years Ago: Smoking and Cancer, pioneers of flight (or fright)”. Scientific American. 283.1 (July 2000): 12.

Christopher, John. Balloons at War: Gasbags, Flying Bombs and Cold War Secrets. Tempus Publishing Ltd., 2004.

Christopher, John. Riding the Jetstream: The Story of Ballooning from Montgolfier to Breitling. London: John Murray Publishers Ltd., 2001.

Delgado, Alan. Victorian Entertainment. New York: American Heritage Press, 1971.

De Syon, Guillaume. Zeppelin! Germany and the Airship, 1900-1939. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Dunn, Rhoda Hero. "The Aeronauts." Atlantic Monthly 103 (1909): 616-617.

Gillespie, Richard. “Ballooning in France and Britain, 1783-1786: Aerostation and

Adventurism”. Isis. 75.2 (June 1984): 248-268.

Glaisher, J., Flammarion, C., de Fonvielle, W., and Tissandier, G. Travels in the Air. 2nd and Revised Ed. London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1871. Extract found in "James Glaisher (1822-1911)". London and Literature in the Nineteenth Century. 18 Jan 2002. Cardiff University.

Mayhew, Henry and Binny, John. The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of Prison Life. London: Griffin, Bohn, 1862. Extract found in "Henry Mayhew (1812-87) and John Binny". London and Literature in the Nineteenth Century. 18 Jan 2002. Cardiff University.

Singer, Bayla. Like Sex With Gods: An Unorthodox History of Flying. Texas: A & M University Press, 2003.

Tucker, Jennifer. “Voyages of Discovery on Oceans of Air: Scientific Observation and the Image Of Science in an Age of ‘Balloonacy’”. Osiris. 2.11 (1996): 144-176.

Van Riper, A. Bowdoin. Imagining Flight: Aviation and Popular Culture. Texas: A & M University Press, 2004.

Verne, Jules. Five Weeks In A Balloon, or Journeys and Discoveries in Africa by Three English Men. Compiled in French from the original notes of Dr. Ferguson. Trans. William Lackland. New York: W.L. Allison, [n.d]. 8 May 2003. University of Adelaide Library.